Softwoods

A forest is a carbon bank, every tree a deposit.

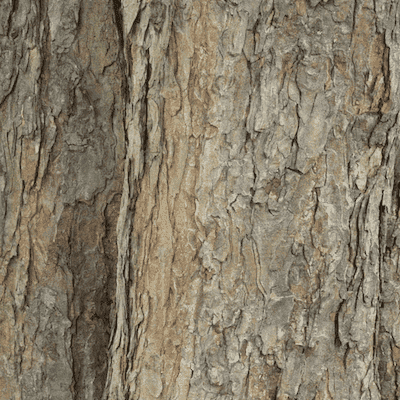

Chestnut trees are large, deciduous trees belonging to the genus Castanea. Native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, these majestic trees can grow up to 100 feet (30 meters) tall, featuring broad, spreading canopies and deeply furrowed bark.

Chestnut trees produce edible nuts encased in a spiny outer shell that splits open when ripe. Known for their sweet, nutty flavor, chestnuts are often roasted, boiled, or incorporated into dishes like stuffing, soups, and desserts.

Historically, chestnut trees have been cultivated for their valuable nuts, timber, and ornamental appeal. Their durable wood has been used extensively for furniture, construction, and fuel. Unfortunately, chestnut trees face significant threats from chestnut blight, a fungal disease that has decimated populations in North America and Europe. Ongoing efforts focus on breeding and genetic engineering to develop blight-resistant varieties.

The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) once dominated the forests of eastern North America, providing essential food for wildlife and humans alike. Its strong, rot-resistant wood was widely used for building, furniture, and fuel.

In the early 20th century, the chestnut blight—a fungal disease introduced from Asia—wiped out an estimated 4 billion American chestnut trees. This ecological disaster transformed the landscape and eliminated a critical resource for wildlife and local communities.

Efforts to restore the American chestnut are ongoing, using innovative methods such as:

Restoring the American chestnut is vital for its:

With advancements in breeding and biotechnology, the future holds promise for the American chestnut. Restoring this iconic tree not only revives a piece of natural history but also offers new economic opportunities and ecological benefits for future generations.

What Is Chestnut Blight?

Chestnut blight is a fungal disease caused by the pathogen Cryphonectria parasitica. This fungus likely originated in East Asia, where native chestnut species are naturally resistant to the disease. The blight was inadvertently introduced to North America in the early 1900s when Chinese chestnut trees were planted in New York's public parks. Unbeknownst to officials, these trees carried the fungus, which spread rapidly and devastated American chestnut populations.

The fungus enters chestnut trees through wounds in their bark, forming cankers that eventually girdle the trunk, killing the tree above the infection site. It spreads through spores carried by wind, rain, and insects and can remain viable for years in the bark of dead trees, making it extremely difficult to eradicate.

Before the blight, the American chestnut was a keystone species in eastern North America, providing essential food and habitat for wildlife and serving as a valuable source of timber. However, the disease wiped out 99% of American chestnut trees by the 1950s, with an estimated 4 billion trees lost. Only a few isolated stands of American chestnuts survive in the remote corners of Kentucky and Tennessee, too gnarled to hold commercial value and shielded from the spread of the blight by their isolation.

Today, efforts are ongoing to restore the American chestnut to its native range. Scientists and conservationists are exploring several strategies, including:

Despite the devastation caused by chestnut blight, advancements in science and conservation offer hope for the revival of this iconic species. Restoring the American chestnut would not only heal ecosystems but also provide economic and cultural benefits, reaffirming its place as a cornerstone of Appalachian forests.

Despite the devastating impact of chestnut blight, millions of American chestnut trees continue to sprout each season from their original root systems, some of which are hundreds of years old. Since the blight-causing fungus only affects the above-ground portions of the tree, the roots remain disease-free. However, once the sprouts grow to a caliper of about one inch by their third or fourth year, the blight forms cankers that eventually kill the young saplings.

To combat this, researchers are crossbreeding the DNA of original American chestnut rootstock with blight-resistant Chinese chestnut varieties. Early results are promising, and the ultimate goal is to produce millions of blight-resistant seedlings to replant native forests and restore the American chestnut population to its former glory.

True American chestnut wood is exceptionally rare and sought after for its stunning light-to-dark tan hues and distinctive patterned grain. Today, most chestnut wood is sourced from reclaimed timber salvaged from old barns and buildings or from submerged logs retrieved from river and lake bottoms.

A key indicator of authentic American chestnut wood is the absence of holes. In contrast, "wormy chestnut," a more common imposter, is identified by its distinctive worm holes. True American chestnut wood commands a premium price, often surpassing other North American hardwoods like oak and walnut in value.

River salvage milling involves retrieving sunken logs from rivers and streams to process them into lumber. This practice became prevalent in the 19th and early 20th centuries when logging companies floated timber downstream to mills. Inevitably, some logs sank and were abandoned due to the difficulty and expense of retrieval.

Advances in technology during the late 1800s allowed for the salvage of these sunken logs using steam-powered log haulers and underwater sawmills. Chestnut logs were particularly prized for their strength, durability, and resistance to rot, making them a popular target for salvage operations.

River salvage milling significantly contributed to the U.S. economy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by providing a valuable source of lumber and creating jobs. However, it caused extensive environmental damage, including disruption of river ecosystems and alteration of natural water flows.

Today, river salvage milling is rare, with increased emphasis on restoring damaged waterways and promoting sustainable forestry practices. Chestnut wood salvaged from rivers remains a prized material, reflecting both its historic value and environmental challenges.

American Chestnut is native to the Appalachian Mountain region of the United States but grows south of the Great Lakes down as far as Tennessee and Kentucky.

Chestnut trees are among the fastest-growing hardwood species, making them an excellent candidate for commercial tree plantations. Their rapid growth, combined with their ability to produce valuable timber and nuts, positions chestnut trees as a highly profitable and sustainable investment for timber growers.

Adopting advanced plantation designs such as geometric spirals can significantly enhance the growth and profitability of chestnut tree plantations. This method leverages natural energy dynamics to promote healthier, faster-growing trees.

Developing and growing blight-resistant American chestnut trees could revolutionize the timber industry in the United States. With the species’ historic reputation for producing strong, durable, and beautiful wood, reintroducing blight-free chestnut trees offers unparalleled financial potential:

Investing in commercial chestnut plantations not only offers financial returns but also supports efforts to restore this once-iconic species to its natural habitat. The combination of innovative plantation methods, blight-resistant varieties, and dual-income opportunities positions chestnut farming as a transformative force in sustainable forestry.

In summary: Chestnut tree plantations present a promising avenue for timber investors and agricultural entrepreneurs. With advanced planting techniques, these plantations can offer high yields, disease resistance, and exceptional returns, all while contributing to ecological restoration and carbon sequestration efforts.

American chestnut wood has long been celebrated for its exceptional strength, durability, and versatility. Lightweight yet incredibly robust, this wood is prized for its straight grain, fine uniform texture, and natural resistance to rot, making it ideal for both indoor and outdoor applications.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American chestnut wood was one of the most widely used building materials in the United States. Its combination of strength, workability, and resistance to decay made it a preferred choice for:

Unfortunately, the chestnut blight of the early 20th century decimated the American chestnut population, making this once-abundant wood extremely rare today. Salvaged chestnut wood, sourced from old buildings and barns or from river salvage operations, is highly sought after and commands premium prices. This reclaimed wood is often used by woodworkers and artisans to create one-of-a-kind pieces with both beauty and historical significance.

Blight-resistant American chestnut hybrids are now being developed through crossbreeding and genetic engineering, offering hope for the restoration of this iconic species. These efforts could make American chestnut wood more accessible in the future, revitalizing its role in sustainable forestry and timber markets.

The restoration of American chestnut trees presents significant economic and environmental opportunities. Blight-resistant hybrids and “blight-free” virgin rootstock from regions like Kentucky and Tennessee are now available for reforestation and commercial planting. These advancements could lead to a resurgence in the availability of American chestnut wood, offering a sustainable resource for the timber and furniture industries while supporting biodiversity and carbon sequestration efforts.

From maple to oak, hardwoods whisper of centuries past, their slow growth a testament to patience and value over time.

Partner with us in a land management project to repurpose agricultural lands into appreciating tree assets. We have partnered with growingtogive.org, a 501c3 nonprofit, to create tree planting partnerships with land donors.

We have partnered with growingtogive.org, a Washington State nonprofit to create a land and tree partnership program that repurposes agricultural land into appreciating tree assets.

The program utilizes privately owned land to plant trees that would benefit both the landowner and the environment.

If you have 100 acres or more of flat, fallow farmland and would like to plant trees, then we would like to talk to you. There are no costs to enter the program. You own the land; you own the trees we plant for free and there are no restrictions; you can sell or transfer the land with the trees anytime.

Copyright © All rights reserved Tree Plantation